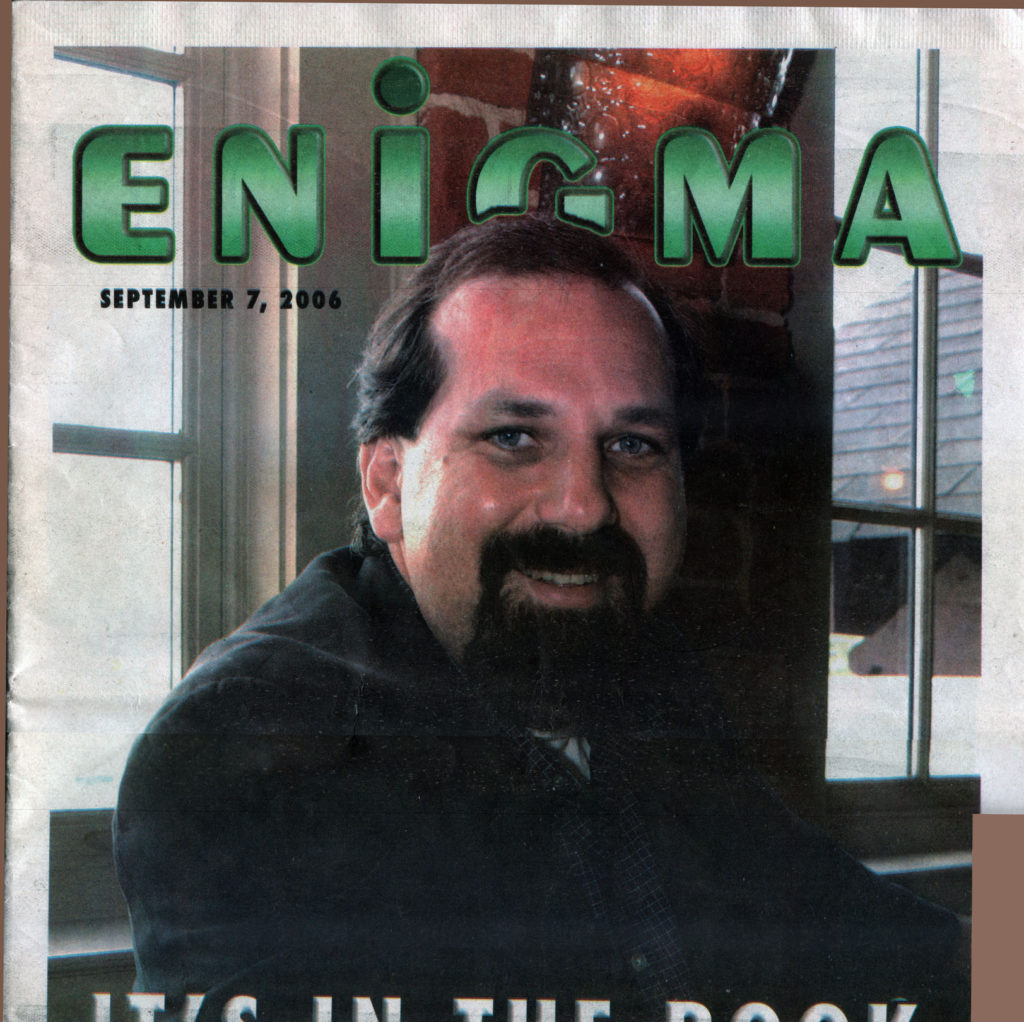

by Dave Weinthal, Sept. 7, 2006

Dean Arnold, a fifth-generation Californian came to Chattanooga in 1982 to attend Covenant College. Upon graduation he began a career in journalism.

For many years he entertained or struck fear into others with his facsimile newspaper, aptly titled “The Chattanooga Fax”. His faxes would be distributed to subscribers tackling some in-depth issues that the daily papers in town would not dare touch. After many years, he put the Chattanooga Fax to pasture. With already one book under his belt, America’s Trail of Tears, he embarked on what could have been a suicide mission. Arnold has authored the most comprehensive history of Chattanooga, interviewing many prominent families and civic leaders, that many consider unapproachable. He was able to do this, interviewing over 50 subjects tracing the city back to its Native American roots, and delve into the long-held belief of a power structure that ruled the town. The labor of love and discovery is here, and it’s called “Old Money New South: the Spirit of Chattanooga.”

When you first came to Chattanooga in 1982 Chattanooga was a much different city than today. In fact they would make a point out of the fact you weren’t originally from Chattanooga. Did you feel accepted right away when you moved here?

I moved here in ’82 and first of all that was the economic nadir of the community. The place looked terrible, and I think Brainerd Road was the hotspot. You also had a little bit of action on Amnicola Highway. Chattanooga has obviously changed cosmetically quite a bit. We’ve had a bit of an economical upturn – not completely. In terms of feeling like an outsider? Sure. I think that’s changed somewhat. I don’t think it’s changed completely. I think we have a ways to go. But my book tries to make the point that if you’re committed to the community and try to make a difference the “power structure” brings you in and embraces you. So I don’t think that’s so much of an issue.

I think there might be incestuous economic dealings, and incestuous vision is probably the bigger problem with Chattanooga – not so much around new blood to be in there and do something; I think that’s allowed. But I think the sense that we’ve got to work hard to bring in new blood, that we’ve got to expand our vision and our vision of what we’ve always done beyond what we’ve always done here. That’s the biggest thing.

When I was doing the Chattanooga Fax, I thought back in the days in the mid ‘90s if I had talked about there being a conspiracy of power structure folks and captains of industry to hold out, to keep out businesses from moving to Chattanooga because it would drive up wages and they didn’t want to have that—people would have looked at me like I was a conspiracy nut, like I was a hate monger. In my book I interview Scotty Probasco and Frank Brock, George Elder and these others who say that that’s exactly what happened. They were talking about their fathers and actually had conversations with their fathers about that problem. And so it’s no longer a conspiracy theory – it’s a fact. And the book deals with that quite a bit. From that perspective, yeah, there was a problem breaking in. We’re talking ‘40s, ‘50s, ‘60s. When the ‘70s came and the early ‘80s we got kicked in the teeth so bad economically that everybody said forget holding people back, we’ve got to do something. It was kind of a day late and a dollar short. We had a lot of work to do.

So you surmised through all the rumor and conjecture that there indeed was or is a “power structure” in Chattanooga?

Yeah. The whole book is about the power structure. I actually have a closing paragraph in the last chapter that sums it up. It basically says it’s actually hard to know exactly who the power structure is or exactly how much power they have, and how it’s wielded, but there definitely is one. But even the power structure players themselves don’t know exactly who each are, or exactly how it works. They just know they’re sort of in this thing. It’s more than urban legend. It’s a reality, but it’s unquantifiable. But I think that’s one of the most interesting things that I learned. The people in the power structure – it’s as big a mystery to them as it is to me. I just had fun with that.

How accessible were the people you interviewed in the book? Your background is in investigative journalism.

Yeah, it was a little bit difficult. If you’re a reporter worth your salt you have that strange ability to buddy up to the person you’re also skewering. I’ve got a little bit of that. I was at a strategic disadvantage because of all the muckraking I had done with Chattanooga Fax. But one of the good things that happened early on was I ran into Scotty Probasco on a street corner, and I told him about my project; that I was doing this book about Chattanooga and was going to interview 50 leading citizens and would he consider being interviewed for the book. He kind of looked me in the eye and sized me up and he must have felt like I was a good bet. He gave me the interview. We had a great time. Never mentioned the Chattanooga Fax – still don’t know if he knows anything about the Chattanooga Fax. His interview helped quite a bit. It was good to go to everybody else and say Scotty Probasco did an interview with me, will you do an interview with me? I don’t want to blow it for the book, but there was one person who didn’t do an interview out of the 50 or so I worked on. When you read the book you’ll find out who that is.

What was your motivation to write this book?

A lot of different motivations. I would have to say, just a love for the city was the bottom root. I love the place. It’s a crazy town – a screwed up town in many ways, but it’s also a very blessed town with extraordinary gifts. It’s just like you love your brother. He’s a goofball sometimes – sometimes he’s great. So I love the city. That was the motivating force.

I’ve always been kind of a historical junkie, and I’ve always been fascinated with origins. I wanted to find out where all the multigenerational family stuff came from. Where do these family fortunes come from? Where did the strange influence of Presbyterianism in Chattanooga come from? Where did this power structure concept originate?

Then I get into literal origins – who was here before the Cherokees and go all the way back to 15,000 B.C. with Moccasin Bend artifacts, which are quite unusual for North America. Also we kind of made a unique discovery. I came across a unique discovery that was made in terms of who were the people here before the Cherokees. They hadn’t been identified when the most recent histories had been written in 1980 by John Wilson and James Livingood. But since then some University of Georgia scholars and some others has done some USGF mapping studying the original manuscripts of the Spanish explorers, and they found out there was a group here preceding the Cherokees called the Napochin. That group preceded them and we’ve got a bunch of commentary about the Napochin Indians from ancient sources. They didn’t know it was in Chattanooga, but they knew it was somewhere. And we figured that out now. It was a groundbreaking discovery.

How were you able to put Scotty Probasco at ease when you first approached him about the book?

Scotty Probasco is a great, big booster of Chattanooga; a really big cheerleader of Chattanooga. My main motivation to write the book was a love of the city. I told him I had this book I wanted to write and it was called, “The Spirit of Chattanooga”, and it’s going to explore the extraordinary nature of Chattanooga. Anybody that’s at a high level of business and someone in the community like Scotty Probasco is, you’ve got to be able to read people, to discern people, where they’re coming from and what their motives are. I think he noticed my motives were for real.

What did you discover about the tribes here before the main settlers moved in?

Actually what happened was the Napochin were living here in about the 1500s there was a terrible drought and famine, and all sorts of problems. They dispersed. Some of them changed to Tuskegee. There was a lot of morphism. The Napochin’s name changed to Tuskegee. There was a Tuskegee up north about an hour from here in North Carolina. There’s also a Tuskegee in Alabama. They kind of dispersed. The place was actually barren for about 150 years. No one lived here. Then Cherokees started to trickle in like John McDonald who married a Cherokee woman and his son, Daniel Ross. Some other Cherokees began to live here and there and dot the landscape here, but not too much. Why that’s significant is people like to say all these Native Americans replaced each other; they all drive each other out – an endless cycle of removal. This research shows that really wasn’t the case. The Cherokees came to a dearth of a land, which wasn’t being used. When we drove them off – we drove them off. We screwed them.

What was the age range of the people you interviewed from these select families?

I also interviewed a lot of elected officials, like Zach Wamp and Bob Corker, Dalton Roberts, and also a couple of foundation heads, cultural-type folks. Larry Ingle, who was a history professor at UTC, the head of the Lyndhurst Foundation, Jack Murrah, the head of the resource foundation, Doug Daugherty. But the lion’s share was the prominent families. I would say the average age was probably 60 to 65.

Did you find their take on the history of Chattanooga different depending on their generation?

I don’t think there was a generational thing. I think the Lookout Mountain crowd has the culture, and I think that culture’s pretty clear. It’s got a lot of good aspects, and it’s got some bad aspects. But it’s a pretty clear culture. I think those guys that are in that culture, whether you’re 50 or 70 or 40 or 80, I think they all have more similarities than they do differences.

After interviewing these people, did you have a more positive outlook? Did you find out what you expected to find? Were there any surprises?

I mention one – that the power structure doesn’t really know exactly who they are and how they work. They really don’t have a grasp on it. It’s certainly not a bunch of guys getting into a room and deliberately changing the city, because it just doesn’t work that way. It does happen in a weird way. So that’s one.

I would say things are a lot more disconnected than we realize. The fact that I did what I did and interviewed all these people, I’m probably one of the most connected people in Chattanooga that there is in the community, and I kind of feel isolated. So what does that mean for the rest of us? I just think sometimes to be human is to feel isolated. I think it’s sometimes a temptation, as just an ordinary guy living in the city, to think there’s a bunch of people somewhere else running everything. I don’t think that’s really the case. I think they’re looking for some kind of connection to humanity and a connection to the community; just like you are. So I would say that the community, just like each one of us as individuals, we could always use a whole, whole lot more connection.

Did you interview different generations of the same family?

I interviewed two Brocks: Bill Brock and Frank Brock; they’re brothers. In terms of the same family line, I don’t recall that I did. I think I also learned that family is extremely strong. Blood is thicker than water, and that’s really one of the things that defines Chattanooga. The reality is most communities in most cites don’t have this sort of thing, and so it’s really that fragmentation and isolation I was telling you about. It’s just far, far worse. It’s a mass of bureaucracy. Chattanooga has more of a human sense to it because there’s more family ties – and that all together is a net plus.

How open and candid were these political figures compared to the old families you interviewed?

I really found most people to be open and honest with me. I didn’t find a contrast between the two. What I found is I think everybody realizes that Chattanooga really needs to grow up really quick. We enjoyed this power structure, kind of small group that we had around for decades that could get in a room and raise a bunch of money real quick and do a bunch of things to help the community in a bind and that kind of stuff, I think because of these Coca Cola bottling fortunes and guys like Jack Lupton and Summerfield Johnston, who are in the Forbes Top 400. So you had massive concentrations of wealth far in excess of your average town this size. So a lot of problems could be solved, a lot of things could happen – and that’s good in its own way. It has it drawbacks. Those people are dying off, and that has run its course, and Chattanooga has got to find an economic identity. I think everyone that I interviewed from Mai Bell Hurley to Jack Murrah to Frank Brock,, George Elder to Scotty Probasco to Tommy Lupton to Bob Corker, Zach Wamp, all of them – they all agree. They all realize we’ve got to move to the next level; we’ve got to get the new blood in there – a new generation of leadership. There’s going to be a broader group of people making decisions. We’re going to have to learn and think and act and communicate in consensus. We’re not used to that in Chattanooga.

Were you surprised they were open to that, or were they kind of conceding the fact?

Yeah, I think they were kind of conceding the fact; and I wasn’t surprised, because it’s kind of a no-brainer. It’s just where we are.

You’ve written the book, it’s been published and getting rave reviews. Are you happy with the finished product?

I was really happy with it. It is absolutely a baby. It was my baby. I obsessed over it for three or four years. I really put my heart and soul into it. Someone was asking me if there was any other book like it in Chattanooga. I said not only is there not another book like it in Chattanooga, I don’t think there is a book like it anywhere else in the country. James Michener has done some similar things, and he’s a far better writer than I am. I’m not comparing myself like that. That’s a similar genre. But he doesn’t do what I did in terms of interviewing all the leading families and going back to their ancestors and telling those stories and kind of asking the question of what happened back then with our ancestors affects us today. There’s a whole different ambiance. The book is very unusual. I’m really proud of it. It’s just a labor of love. I worked really hard on it.

How would you describe the book – more historical or was there an personal agenda?

It started out without an agenda. It’s one of the things that makes it interesting. It started out – the first agenda is make it interesting. If you’re a communicator and a writer, you actually want to sell books, so it’s got to be interesting. So, the book’s interesting: let’s tell some fun stories. Let’s lead with the lifestyles of the rich and famous, because that’s where people are coming from. But let’s also get into the interesting, fascinating history – what’s behind everything, and what creates the culture around here. There’s some fascinating chapters on Presbyterianism here, the church policy and how that affects the government.

The second agenda was what makes Chattanooga unique and what makes it extraordinary. Those were two very broad things. Let’s have fun and let’s see what makes Chattanooga unique. Then I sort of let the story tell itself. The product that emerged, I was really happy. As an artist, I really didn’t know exactly what I was doing. My previous book, America’s Trail of Tears is a straight historical narrative. This book, I wasn’t sure how it was going to work. It was really more like an artistic creation. It goes back and forth throughout the book, and it catches things from different angles. It’s really not a story from beginning to end. It was a whole bunch of stories kind of all poured together in a wild stew.

What was the thread that bound them all together?

The uniqueness of Chattanooga. The families and the commitment to family that has been a defining thread in the history of the city. And the religious impact on Chattanooga. The Bible Belt, fundamentalist culture, but more so than that, a very extraordinary and unusual impact of the First Presbyterian Church from the very beginning until now.

The book is out now and getting attention. Where do you go from here?

I’m moving to Philly. And I’ve got personal reasons to go there – to be closer to my two children, but I’m also working on a movie script. Given that I’m in that area, Philadelphia and the East Coast is probably a better land of opportunity for me now than Chattanooga. I’ve got mixed feelings on it. I just got to the point where I’ve written the book on Chattanooga and now I’m leaving. I’ve got friends and contacts and relations here, but in another sense it’s probably good. I won’t be guilty of the same things as some of the folks in the book that was a problem, like getting out there and bringing some fresh blood in. So, I’m looking forward to the opportunity. I’ll be in Chattanooga every once in a while, but I have a feeling I’m moving on.